How women was perceived in the Yazidi society of the 19th century. Marriages and Divorces

Murat Gokhan Dalyan

Cabir Dogan

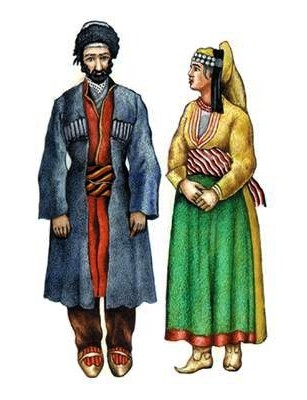

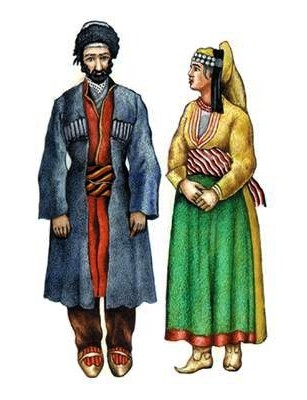

Marriage and Weddings Various factors were taken into consideration when marriages were being arranged in Yezidi society. The most important of those was that the bride and the groom had to be members of the same caste. Thus, a woman could not marry a groom whose caste was higher or lower on the ladder than her own stratum . Someone from a Sheikh family could only be married to someone from another Sheikh family. If there were no suitable girls available for marriage from a Sheikh or a Mir family, then marriage to another girl was allowed, but she still had to be of the same stratum. This resulted in the phenomenon of betrothal in the cradle, that is to say, marriage arrangements made when the respective bride and groom were only infants. According to Roger Lost, the only rationale behind the principle of not marrying outside one’s own caste and the prevention of inter-stratum mobility was to protect the privileges of the higher strata . The caste system still in place in today’s marriage arrangements within Yezidi society constitutes one of the most important points of criticism against the Yezidis . Young girls in Yezidi society have sometimes been married in the form of berdel without bride price, or without berdel to end conflicts between tribes, to end blood feuds, or to form alliances. In these extraordinary situations, the final say over whom the girl would marry belonged to the father, who was considered to be the head of the household, and the girls could only marry someone he deemed to be appropriate. A Yezidi girl was not allowed to marry someone from another nation either. However, in some periods Yezidi girls are known to have married with Muslim men and adopted their religion. The average marriage age was around 12-13, shortly after the children entered puberty. As polygamy was allowed, women were sometimes co-wives when they married. Differently from Muslims, Yezidi men are allowed to marry up to five women. However, mirs could have as many wives as they liked . According British missionary Fletcher, who visited Yezidi regions in the 1850s, mirs had about twenty wives on average. The number of wives a mir had was proportional to his wealth. The families on both sides of the marriage first had to gain the approval of the Sheikh or another leader to whom they were attached, in return for a gift. Otherwise, their marriage would not be considered a respectable one by society. Religion did not play much of a role in Yezidi wedding ceremonies. In Yezidi society, getting married in April was not allowed, but this rule did not apply to Qawwals . They could get married any month of the year. On the wedding day, the bride was let out of her house by her mother, her face veiled with a bridal face, and sent to her husband’s house on horseback, with friends and relatives accompanying her. The bride was not allowed to see the groom until the nuptial night .When the wedding convoy arrived at the groom’s house, a loaf of bread was broken into pieces above the Yezidi bride’s head, so that the bond of love between the wife and husband would be eternal. The idea that women need to show absolute submission to men’s authority was a powerful norm in the society. Thus, to symbolize a bride’s submission to her husband’s authority, the groom threw a small piece of rock into the entrance of the marriage house . The bride remained in her bridal veil during the whole ceremony, and the marriage was solemnized on the third night of the wedding by a Qawwal or another Yezidi religious scholar. Both sides were asked to take a vow, then their faces were painted red and they were asked to break a branch that they held in their hands. Then, the Qawwal asked the two sides to swallow dust brought from the shrine of Sheikh Adi. During this ceremony, the bride’s face was open. After the ceremony, the groom gave the bride a present, which was either a hand-made headscarf, a bracelet, or a ring . At Yezidi weddings, men and women used to dance together. If the bride and the groom lived in different villages, then the bride had to visit all the temples in her husband’s village, even if they were churches. At the end of the 19th century, the Ottoman state aimed to keep records of the marriages between Yezidis like those among other Muslims, because they were treated as Muslims by the state and the state wanted to see them kept within the circle of civilization. Thus, from 1877 onwards, all solemnizations were to be carried out by muftis. This arrangement gave hope to those young women who did not want to get married with prospective grooms their fathers had chosen . Yezidi leader İsmail Bey, who was at first opposed to this new arrangement, eventually accepted that marriages be performed by qadis, fearing that western modernization would fragment Yezidi society as well. However, this regulation was not really followed by the Yezidis. In later years, imams replaced qadis as marriage performers, but they insisted that the Yezidis recite the Kalimah Shahadah (that is to say, profess that they are Muslims) prior to the ceremony, which left the impression among the Yezidis that they were being forced to convert, and so they stopped having imams solemnize their marriages . Eventually, official marriages became the norm. Particularly from the final quarter of the 19th century onwards, the average marrying age for women started to increase. More frequent contact with the outside world and more widespread education were the primary forces driving this change .

Divorce Like in many other societies, divorce existed within Yezidi society as well, but required the presence of certain conditions, the primary among them being adultery . If the adulterer was the wife, she was killed immediately, and the marriage bond was considered severed. If, on the other hand, it was the husband who committed adultery, he had to pay three times the regular blood money to his wife’s family. If he did not have the financial means to make that payment, he too was killed immediately. Other than that, if the husband did not attend to the needs of his wife for one year, or left her, these were also considered to be valid reasons for divorce. Thus, if the husband went away, even for work related purposes, he was considered to be divorced upon his return, and was not able to find a woman to re-marry. If people helped him find a girl or a woman with whom he could marry again, then they were considered his accomplices in adultery . The power to divorce, like in other patriarchal societies, was given exclusively to the men. If a Yezidi man put three pebbles in his wife’s hand saying, in the presence of three witnesses, “I divorce you, I divorce you, I divorce you”, then he was considered to have divorced his wife. After this stage, the husband was not allowed to come together with his ex-wife, and could not claim any rights over her. Another way to divorce was as follows: if a Yezidi woman left her husband’s house and returned to her father’s house, she was considered to be divorced and half of the bride price initially paid to her family was re-paid to the ex-husband. If, at this stage, she married another man, the ex-husband collected half the bride price from the new husband. In all matters concerning divorce, the mir was the greatest authority.

Tags:

How women was perceived in the Yazidi society of the 19th century. Marriages and Divorces

Murat Gokhan Dalyan

Cabir Dogan

Marriage and Weddings Various factors were taken into consideration when marriages were being arranged in Yezidi society. The most important of those was that the bride and the groom had to be members of the same caste. Thus, a woman could not marry a groom whose caste was higher or lower on the ladder than her own stratum . Someone from a Sheikh family could only be married to someone from another Sheikh family. If there were no suitable girls available for marriage from a Sheikh or a Mir family, then marriage to another girl was allowed, but she still had to be of the same stratum. This resulted in the phenomenon of betrothal in the cradle, that is to say, marriage arrangements made when the respective bride and groom were only infants. According to Roger Lost, the only rationale behind the principle of not marrying outside one’s own caste and the prevention of inter-stratum mobility was to protect the privileges of the higher strata . The caste system still in place in today’s marriage arrangements within Yezidi society constitutes one of the most important points of criticism against the Yezidis . Young girls in Yezidi society have sometimes been married in the form of berdel without bride price, or without berdel to end conflicts between tribes, to end blood feuds, or to form alliances. In these extraordinary situations, the final say over whom the girl would marry belonged to the father, who was considered to be the head of the household, and the girls could only marry someone he deemed to be appropriate. A Yezidi girl was not allowed to marry someone from another nation either. However, in some periods Yezidi girls are known to have married with Muslim men and adopted their religion. The average marriage age was around 12-13, shortly after the children entered puberty. As polygamy was allowed, women were sometimes co-wives when they married. Differently from Muslims, Yezidi men are allowed to marry up to five women. However, mirs could have as many wives as they liked . According British missionary Fletcher, who visited Yezidi regions in the 1850s, mirs had about twenty wives on average. The number of wives a mir had was proportional to his wealth. The families on both sides of the marriage first had to gain the approval of the Sheikh or another leader to whom they were attached, in return for a gift. Otherwise, their marriage would not be considered a respectable one by society. Religion did not play much of a role in Yezidi wedding ceremonies. In Yezidi society, getting married in April was not allowed, but this rule did not apply to Qawwals . They could get married any month of the year. On the wedding day, the bride was let out of her house by her mother, her face veiled with a bridal face, and sent to her husband’s house on horseback, with friends and relatives accompanying her. The bride was not allowed to see the groom until the nuptial night .When the wedding convoy arrived at the groom’s house, a loaf of bread was broken into pieces above the Yezidi bride’s head, so that the bond of love between the wife and husband would be eternal. The idea that women need to show absolute submission to men’s authority was a powerful norm in the society. Thus, to symbolize a bride’s submission to her husband’s authority, the groom threw a small piece of rock into the entrance of the marriage house . The bride remained in her bridal veil during the whole ceremony, and the marriage was solemnized on the third night of the wedding by a Qawwal or another Yezidi religious scholar. Both sides were asked to take a vow, then their faces were painted red and they were asked to break a branch that they held in their hands. Then, the Qawwal asked the two sides to swallow dust brought from the shrine of Sheikh Adi. During this ceremony, the bride’s face was open. After the ceremony, the groom gave the bride a present, which was either a hand-made headscarf, a bracelet, or a ring . At Yezidi weddings, men and women used to dance together. If the bride and the groom lived in different villages, then the bride had to visit all the temples in her husband’s village, even if they were churches. At the end of the 19th century, the Ottoman state aimed to keep records of the marriages between Yezidis like those among other Muslims, because they were treated as Muslims by the state and the state wanted to see them kept within the circle of civilization. Thus, from 1877 onwards, all solemnizations were to be carried out by muftis. This arrangement gave hope to those young women who did not want to get married with prospective grooms their fathers had chosen . Yezidi leader İsmail Bey, who was at first opposed to this new arrangement, eventually accepted that marriages be performed by qadis, fearing that western modernization would fragment Yezidi society as well. However, this regulation was not really followed by the Yezidis. In later years, imams replaced qadis as marriage performers, but they insisted that the Yezidis recite the Kalimah Shahadah (that is to say, profess that they are Muslims) prior to the ceremony, which left the impression among the Yezidis that they were being forced to convert, and so they stopped having imams solemnize their marriages . Eventually, official marriages became the norm. Particularly from the final quarter of the 19th century onwards, the average marrying age for women started to increase. More frequent contact with the outside world and more widespread education were the primary forces driving this change .

Divorce Like in many other societies, divorce existed within Yezidi society as well, but required the presence of certain conditions, the primary among them being adultery . If the adulterer was the wife, she was killed immediately, and the marriage bond was considered severed. If, on the other hand, it was the husband who committed adultery, he had to pay three times the regular blood money to his wife’s family. If he did not have the financial means to make that payment, he too was killed immediately. Other than that, if the husband did not attend to the needs of his wife for one year, or left her, these were also considered to be valid reasons for divorce. Thus, if the husband went away, even for work related purposes, he was considered to be divorced upon his return, and was not able to find a woman to re-marry. If people helped him find a girl or a woman with whom he could marry again, then they were considered his accomplices in adultery . The power to divorce, like in other patriarchal societies, was given exclusively to the men. If a Yezidi man put three pebbles in his wife’s hand saying, in the presence of three witnesses, “I divorce you, I divorce you, I divorce you”, then he was considered to have divorced his wife. After this stage, the husband was not allowed to come together with his ex-wife, and could not claim any rights over her. Another way to divorce was as follows: if a Yezidi woman left her husband’s house and returned to her father’s house, she was considered to be divorced and half of the bride price initially paid to her family was re-paid to the ex-husband. If, at this stage, she married another man, the ex-husband collected half the bride price from the new husband. In all matters concerning divorce, the mir was the greatest authority.

Tags: